- Home

- Jess Arndt

Large Animals Page 2

Large Animals Read online

Page 2

“Can you help her?” said Joelle, looking at me hopefully for the first time since Moonwalk. Joelle had money but it was all glommed up in something, her father probably.

I thought about my empty wallet, my art school economy. I scrubbed the ticket out of my pocket and handed it over slowly.

“Three dollars and twenty-four cents?” said Joelle.

I’d painted the Taj Mahal once in a class. My dome had a nice full onion shape but those moon-facing spires that lined the central tomb had confounded me. Somewhere around their midsection they’d rebelled—sticking in every direction but up. My art teacher threw out his hands.

This is all about Love! he’d said, pacing. And Sacrifice! You’re so terrestrial. You’re scared to leave the ground!

I looked at my spires, their tips lopsided and heavy, tugging down toward earth. Boobs, I’d thought. I was too embarrassed to say my Taj was already on the moon, that’s how I’d understood it in the first place.

Contrails

I was going to change everything. The feeling beat through me with its smothering pulse. I’d been waiting to change everything for an eternity, thirty-one years, a very long time. I was sure this meant what I was going to do would change very little. Still I could think of nothing else. I’d spoken to the surgeons—or at least one surgeon, a rising star with a Mad Hatter’s throne in his condo-ish waiting room. The chair spooked me.

Now I was going to do it.

As the date approached, my preoccupation grew. I’d purposefully trap myself sideways in empty windows or mirrors, trying to chase down the future me. I had no idea what to expect, except hopefully: Lothario, pleasure-seeker, and, of course, famous author, household name recognition, writing books that made not just people but their cells cry.

This period was full of lasts. Last time go to this or that restaurant or take the E train to therapy, last four a.m. car service in sway of alcohol-induced feelings, last optimistic but still shittily fitting shirt, last time to see so-and-so before the change.

I was also having send-off conversations in my head. If I’m honest they mostly copied the one I’d already had with my therapist.

“Well, goodbye,” she’d said. “Next time I see you you’re going to feel so motherfucking free!”

I was embarrassed when she said it.

“Ta-da!” I’d said, bolting for the door.

But it had become a model.

I went out to dinner with S. at Thai Me Up. We sat inside at a plastic outdoor table and drank tiny glasses of water. We had sheltered a heavy flirtation once and now it was settled but seeing each other still kicked up dust clouds.

S. was back with her ex and, as she put it, having the best sex that they could have, which left a little trapdoor swinging open. Staring over her perfect shoulder, I scanned all of the possible pitfalls, inadequacies, faulty equipment in their “dynamic” and plugged the data into a mental Excel sheet against mine.

Certainly I measured up (surpassed) in many ways—but there were other activities, behaviors, proclivities that, if I was radically fair, might not have favored me. I brushed them back. The fact remained, I was about to change everything—and who knew who might pop out on the other side?

Our food came and I sucked at my Thai iced tea like a jungle guide pulling out viper venom from a stump. Things had become very sharp. My actions were bolder and less tethered to anyone I had been or anything I had ever done. My body did not yet work better but I padded around in it as if it did, hoping people would notice.

“What did you want to tell me?” S. said.

A gosling surfaced in my stomach and shook its greasy head. I ducked down, my neck broiling. I looked at the well-mopped tile floor. Were my New Balance dirtied permanently? I wondered, or could I, with some soap and water, return them to like-new?

“Ummm,” S. said, “hello.”

My hand was doing that flutter. I pressed down on the stem of my fork. Hurling it across the room felt like my only option—there was no way I could get the squirming tines up off the plate to my mouth.

That night I couldn’t sit still. My earlier behavior was not an example of how someone about to change everything should act. I should make some calls, I thought. I pulled a half-finished Modelo from the fridge—someone had jammed a napkin in it—and scrolled through my address book.

The window was open, the elm leaves flipping up, showing off their white bellies. I stared across at the dark apartments and air conditioners from my position on the third floor opposite. For an instant I felt aware of a great resistance, something bigger than me. Night made me dissolute like drinking did. Put a stretchy space between my synapses—pushed on my legs or arms until there was no body, just black ether lapping at milky shores.

I called V.

It was east to west so it was okay. One a.m.

“What do you want,” she said. She was at a party. Things crashed jovially in the background.

“I wouldn’t have picked up,” she said. “But I’d erased your number and thought you might be the pot dealer.”

“Oh,” I said. “Do you have a minute?”

I was only interested in calling people I had slept with or dated, people who if they knew I was about to change everything should want to give me send-off bon voyage and all that happy landing et cetera et cetera jazz.

With V. I was going very far back, but in my new accounting, it made sense that the women who had known me longest should have the most time to adjust.

“I’ve been thinking about giving a little send-off party,” I said. “Or maybe I mean like a final viewing.”

“A what?” She seemed suddenly disattached from the phone. “No no, it’s not him,” she said.

“A final viewing. Before I change everything.”

“Are you doing a lot of drugs out in New York?” she said. “Diet pills? MDMA? Mushrooms? Glues?”

“You thought I was the drug dealer,” I said. “As in you called him.”

“A final viewing is what you give someone who’s dead,” she said. I heard glass breaking. “Are you dying?”

“You’ll be the first to know,” I said.

I opened another Modelo, gazing into the refrigerator’s chilly rib cage. When I was a kid it occurred to me that I might be a very corrupt person, a murderer even. Just the word, every time I thought it, gave me a hot little shock. One day the knowledge was shoved between the other things I knew about myself—okay at soccer, desperate for sugar, a loner. I was nudging a body out to sea, as I had at sleepaway camp that famous summer when a decomposing shark washed up on the beach near our tents and all night it was my job to push the rubber flesh back against the tide with a board.

This terrible power made me shyer, more self-effacing. I was very concerned with keeping myself in check and performing the daily rituals that I manufactured so that others would be safe.

I described this one night to a girlfriend, T., who often let me get drunk and cry and rip up serviettes against this bar top or that bar top and tell her just these sorts of things. But she wanted to be a social worker so I didn’t feel too bad.

“What if the fantasy really had less to do with your capacity for destruction and more to do with saving everyone?” she said.

I didn’t know what to think. It was true that as soon as a “dark thought” occurred, I threw myself into the solution, eagerly murmuring words and moving objects around in

the dirt.

Her number wasn’t in my phone but after some digging, I pulled out an old journal marked “2000.” Just its battered face gave me the creeps. I extricated the number with tweezers, three-thirty a.m. Central Time.

Her wife answered.

“Fuck you for calling so late,” she said. “You know we have kids, or you would know if you called more. Did you finish your book?”

“I gave it up,” I admitted, but she had already put down the phone.

I turned my receiver up to max.

I could hear all the way through their Chicago apartment. Their parquet floors and the hot breath of the babies next to them, their macaroni fingers clasping and unclasping.

“. . . yeah, same old thing.”

I listened to them sleep awhile in the dark.

Jeff

Boy do I wish I lived in the Penthouse 808 Ravel. Whenever I walk by its ample surfaces, its hacienda-style balconies and black moribund palm trees, a shiver runs through me. I learn things by relation. For example, now I write moribund—it sounded plausible, but who knows? Better to have said doomed, expiring, or how about at the end of one’s rope?

The windows are always dark when I cruise down Hamilton Avenue, carefully peering up at what might one day be mine. Picturesque barely cuts it. The oily swath of the Raritan glimmering so meanly. Like a zipper? “Man vs. Machine,” it says on the bordering fence—a relic of times gone by. “Man is machine,” I mutter. But even that thought is years late, barely worth repeating.

But Penthouse 808 Ravel has promise. Shag carpet. Doors that shut heavily. I have sexual feelings about Penthouse 808 Ravel. Ligature feelings. Relational feelings, knots, bandages. I want to look at the floor plans. Even now I can smell the mimeograph ink that reminds me, in a sharp inhalation, of last night’s freshly snuffed-out sky.

I work across the street at the state university. So does Sheila. I think that’s a great name. If I had a pet I’d name her Sheila. My knees have gotten a little sweaty now, bringing her up. Soon you’ll want to know what the deal is. What’s up with you and Sheila? If I murmur nothing, you’ll squint and frown—It’s okay, you’ll say, you can tell me. Then slowly at first, but soon enough, as if an ambulance is screaming behind you, you’ll get irate—Why’d you even bring her up? Now get out of the lane, and let the poor fucker drive.

I can’t imagine ever needing an ambulance at Penthouse 808 Ravel. Sure, it’s a decadent place. There will be a series of indulgences. A party where all of us from the state university’s English department show up in sweaters on top and nothing down below. Not cardigans either. Big hairy sweaters, mohair—or, better yet, horse. Quaker stuff. Holy Roller stuff. At Penthouse 808 Ravel each window has its own private balcony, a place to air your parts. This is also where they keep the moribund palms. I can just picture it, some new gawker walking down Hamilton, taking my place even, getting misty-eyed about Penthouse 808 Ravel, and then bang! between the palms—it’s Buzz Snyder from Vic Lit, showing his rolls.

Yes, I did have dinner with Sheila. Yes, I did approach her on false pretenses, the false pretenses being: Dear Sheila, I am on my last nerve, I’m begging you please give me some great advice about these lesbian circuit parties I keep attending and the women who are always loitering outside my Subaru Outback 1999, begging for a ride. Sheila was happy to do it, she said. More than happy to do it. Which brings me to another question. Why Sheila and why not the state of Nevada? I personally think the comparison is obvious.

But this isn’t even what I wanted to talk to you about. There’s something more pressing, something I call “Jeff.” Let’s forget about Penthouse 808 Ravel and Sheila, travel back to before the state university, before my name had “Part-Time Lecturer” attached like a plume to the end of it.

The first time I met Lily Tomlin she was so nice. She called me Jeff. “Hi Jeff,” she gushed. I’d been her bartender but she only drank water. “Hi Lily,” I blushed back. What a warm handshake, what a firm and knowing grasp!

“Wow!” my pal said from her barstool. “Is she progressive or what? She didn’t even bat an eyelid!”

“I think she just thought my name was Jeff,” I said.

That was the only time I met Lily Tomlin, our solo tête à tête. But Jeff stuck. Actually Jeff had been trailing me for some time. My box was stuffed with Jeff A________ bills and junk mail. Jeff was horrible, like an insurance salesman. That’s how I pictured him—thick neck, coarse red fur sprouting from his ears. I knew he wore a Mormon-white short-sleeve button-down and that his lips had zero color but were the texture of banana peels stretched tight.

Jeff gave me the heebie-jeebies.

How to then explain the small satisfaction at reading my universe-generated new name? I mean it’s very similar, first two letters—same. Next two letters—not same, but double, which leads me to an auxiliary concern: is f intrinsically more masculine than s?

It felt like a consolation gift. Like the universe saying, Hey, sorry about that boob thing. Oh, and we kind of flubbed it dividing the world in half, and language as enforcer of binary divide? Yeah. Not to mention bathrooms. OOPS. But gosh, well . . . here’s Jeff.

Other days the cosmos didn’t speak to me. Things seemed more mundane. Jeff was just . . . there. But it couldn’t be some clerical error. Lily had said it too, and she wasn’t linked via paper trail to the unglamorous annals of my bill-paying life. Still the Jeff thing continued. I called to reschedule a surgery again and the receptionist was effervescent. “Hey Jeff!” she bubbled.

“No no,” I feebly protested. She seemed let down at the news. People liked Jeff.

Plus—if, as I correctly guessed, we do not live in a benevolent universe, then there was only one conclusion left. I was purposefully muffling the last two letters of my one-syllable tag; I was prank calling my own name.

My father always told me I had marbles in my mouth. Wait, no: “Put marbles in your mouth,” he said. “Put marbles in your mouth every day and talk for ten minutes. It’s essential to be c-l-e-a-r.”

Marbles, how 1950s, like I just had them lying around. But I admit, thinking of it now sounds kind of nice—smooth hard gobs of color rolling around my gums and tongue. What would Sheila think of that? Hey Sheila, I’d say, whatcha doing this Friday? It’s Jethhh.

Sheila again. I can’t get away from the “now,” from the state university and her office ladies, her Scarlet Knights. The other day a famous writer came to talk to us. They’d even made a movie out of her book. She gives a packed reading and at the end she says she wrote the book because she wanted to talk about something that was unreported: male rape.

I agree with her. Of course I do. Then, rushing toward the transit stop, I miss my train. No problemo. I want a substantial drink. Sitting under the trestle in a chain BBQ joint with carbon copies of my students jammed around me, my mind drifts. What’s going on at Penthouse 808 Ravel? I wonder. I’ve never seen anyone enter or exit the place, but I’m sure it’s a pleasure picnic—deluxe fun. Just thinking about it feels good. I order fries and sauce. A guy to my left is flirting with his girlfriend. “That asshole,” he says about someone else. He rubs his finger down her hair. “I should just fuck him in the ass.”

I snap shut like a clam. It’s a hostile universe and these overgrown kids, my best and brightest, are all violent offenders with newly thickened arm hair, whispering sweet nothings into their sugar-soaked Texas teas.

Still an hour until my train, everything true and mean around me. It’s even sleeting; I see it through the glass. I go to pee. A big BBQ joint kind of door. Shiny tiles. At the sinks, a familiar squadron of girls who giggle as I approach. In the mirror—oh god, it’s Jeff. Hair like a scrub brush. Perv gleam in eye. Flat dry fingers holding wads of receipts.

Sitting back on my stool I am sweaty and red. The rapist and his girlfriend are waving sticky ribs at each other and canoodling. Jeff, Jeff. He needs a lesson, someone to give him a firm talking-to. I imagine bending him over, his pleated pants going tight. No, it’s okay! Lesbians can talk about fucking men in the ass, can talk about teaching them a lesson, about giving them a “firm” talking-to.

You get it. Extra points if they’re straight and white, which Jeff of course is.

For the next week I dream about Jeff. He begs me to do all kinds of humiliating things. Tease me about my cuticles, he says. They’re so flaky and hard. Make me eat cereal with no hands straight from the box. Tell me I

have a bad memory. Put my head in a bidet. Now pull it out and put marbles in my mouth. In my dreams, these activities and more take place at Penthouse 808 Ravel.

Then it’s spring break. I go on a wine tour. We stare into the big sweaty vats of red. “Wine fermentation,” the expert says, “happens when all of the individual grapes explode against the walls of their bodies.” How nice, I think, for them.

I ask Sheila to dinner again. This time to a Mexican joint—well applauded, et cetera. First we park and saunter along the banks of the Raritan. Or at least along a pathway that occasionally comes in view of it.

“What’s going on with your circuit-thingies,” she says. She has on open-heeled flats that slap-slap as she walks. Her wildly weather-inappropriate footwear seems promising.

“Oh nothing,” I yawn. I really haven’t been getting much sleep with all my Jeff dreams. They’re getting worse. The things I’m doing to Jeff are ugly. “Actually, Sheila,” I say. “This might come as a surprise, but my Subaru stops for you.”

Slap-slap. And that greasy river, god it looks good.

Over chicken chimichangas I pop it to her. “Do you like Lily Tomlin movies?” I say. This will be my segue.

“She hasn’t been in that many movies,” says Sheila. “She’s pretty much a TV actress if you ask me.”

That night I can’t sleep, period. I play the rest of our date over and over in my mind—the salsa verde that splotches onto my pants, the way Sheila drops her cactus-decorated napkin down. “Oh,” she says, touching the bag of air, the wasteland of nothing, in my crotch. “Oh my,” she giggles, “you’re large.”

Poor Sheila, I’ve been waiting for women to tell me this my whole life. Is this why I pay the check silently and drop her off three blocks from her house, even though I know full well where she lives? Sleepless, I watch myself push marble after marble into Jeff’s ever-expanding ass. I’m hurting him. I know I am. Somebody help him! I think. But he has everything.

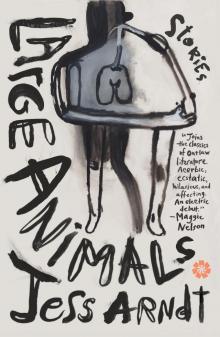

Large Animals

Large Animals